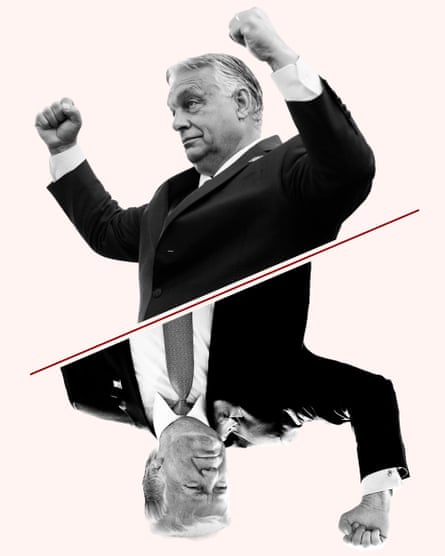

He is the strongman who inspired Trump – but is Viktor Orbán losing his grip on power?

On a sunny April afternoon in Budapest, a handful of reporters crowded around the back entrance of the Dorothea, a luxury hotel tucked between a Madame Tussauds waxworks museum and a discount clothing store in the city’s walking district.

Most had spent hours outside the hotel, hoping to confirm reports that Donald Trump Jr was inside. News of his visit had leaked two days earlier, but much of his agenda remained shrouded in secrecy, save for a meeting with the Hungarian foreign minister.

Reports had also circulated of a closed-door speech the US president’s eldest child and Trump Organization executive was slated to give on bridging governments to the private sector at the five-star hotel reportedly owned by the son-in-law of Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán.

Few other details emerged from the visit. But it was a hint of the outsized role that this small central European country, home to 9.6 million people, is playing in the US’s political conversation.

Trump and those around him have long talked up Orbán’s Hungary, depicting it, in the words of one Hungarian journalist, as a sort of “Christian conservative Disneyland”. The veneration of its alliance of populism and Christianity has persisted, even as the country plunges in press freedom rankings, faces accusations of no longer being a full democracy, and becomes the most corrupt country in the EU.

As Kevin Roberts, the head of the Heritage Foundation thinktank that produced Project 2025, a far-right blueprint for Trump’s second term, once put it: “Modern Hungary is not just a model for conservative statecraft, but the model.”

Orbán, the prime minister who once described Hungary as a “petri dish for illiberalism”, has been lauded by Trump’s former adviser Steve Bannon as “Trump before Trump”. The US vice-president, JD Vance, once characterised Orbán’s purge of gender studies in academia as a model to be followed.

The US president last year called him a “very great leader, a very strong man”. He added: “Some people don’t like him because he’s too strong. It’s nice to have a strong man running your country.”

Since Trump began his second term in January, the adoration has seemingly turned to emulation at a frenzied pace. Trump, like Orbán before him, has seized on state powers to pursue rivals, embraced dark rhetoric to demonise political opponents and purge “wokeness” from institutions, in what analysts described as the Orbánisation of America.

For rights groups, journalists and activists in Hungary who have long pushed back against the steady erosion of rights by arguably the modern world’s most successful populist leader, the parallels are eerie.

Over the past 15 years they have challenged a playbook that has now gone global, turning them into a singular source on how Americans – and others around the world – can fight back in the face of democratic backsliding.

“Sometimes it might seem kind of tempting to say: ‘OK, we’re just going to make this compromise, and it might go away,’” said András Kádár of the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, a Budapest-based NGO. “But the Hungarian example shows that they always go one step further; we always hit new rock bottoms. It’s very important to fight every inch and bit of this process.”

Much of what Orbán is doing follows in the footsteps of Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan or Russia’s Vladimir Putin, he said. But one crucial difference explained why Hungary had captured imaginations in the US, Kádár said. “It’s unprecedented in the sense that you have a full-fledged democracy … in the heart of the European Union, which very consciously chose to go this way.”

In the course of Orbán’s 15-year rule, there is little his government hasn’t tinkered with. After targeting judges and recasting electoral policy to make it harder to oust his party, universities were purged of gender studies courses and public institutions were put under the control of Orbán loyalists.

His critics have accused him of using state tenders to line the pockets of loyalists and of wielding state subsidies to reward pro-government media outlets and starve critical media. Some of the weakened media outlets were later snapped up by entrepreneurs loyal to Orbán and transformed into government mouthpieces, with his Fidesz party and its loyalists now estimated to control 80% of the country’s media.

Throughout it all – in an echo of a strategy that would later be replicated in the US – there was one constant.

“This whole process has been going on behind this smoke screen of hate propaganda, with different targets,” said Kádár, pointing to Orbán’s targeting of Brussels and the EU as well as migrants. “Then they say we need all these powers, these unchecked and uncontrolled powers to protect the people from those enemies inside and outside.”

When it comes to the US, many in Budapest highlighted the differences in how things were playing out. “Compared to what’s happening in the United States, here it was rather slow,” said Péter Krekó, the director of the Political Capital Institute thinktank. “So here it’s more like the frog boiling in the water model, while in the United States, I think it’s a coup, practically.”

Hungary’s transformation, however gradual, has been striking. At the start of the 21st century, the country was a regional leader when it came to the quality of democratic institutions and their independence. It is now the region’s worst performer democratically, after what Krekó described as the “Hungarian propaganda machine” drilled the government’s line into people.

“It’s all over the country, on every billboard, radio spots, on TV. It’s an Orwellian campaign, but on many topics it can shape public opinion very efficiently.”

What had emerged was a country where the notion of who belongs had been recast, said Ádám András Kanicsár, a journalist and LGBTQ+ activist.

“The government has an idea of who is a proper Hungarian and who is not,” he said. “And in the last 15 years, this picture has been narrowed down more and more. Right now, you are a proper Hungarian if you have two children, you are white and Christian and have a job, and are living in a happy marriage. And this is the only way to be a good Hungarian.”

This year Orbán and his backers banned all public LGBTQ+ events. Looking back, Kanicsár said the community had long been too passive in asserting their rights.

Although the government’s ban led many in the community to speak up, they were now on the defensive, explaining why their hard-won rights needed to be protected, rather than pushing for advances such as same-sex marriage. “They have the narrative now,” he said, referring to the government. “We can’t bring new topics to the table.”

The government’s most recent amendment also enshrined the recognition of only two sexes in Hungary’s constitution, wiping out the identities of people such as Lilla Hübsch.

“Basically my existence right now is unconstitutional, which is kind of crazy,” said the trans activist as she joined Kanicsár at a bustling coffee shop in Pest, the part of the capital that flanks the eastern bank of the Danube.

For Kanicsár, it was a reminder of how many in Hungary – and around the world – had long assumed progress was inevitable.

“It’s a big mistake. We think that history is a narrow line upwards, that we are always getting better and better, more liberal, more democratic,” he said. “But we can always lose it. And if you have it and you lose it, it can be really hurtful.”

The banning of Budapest Pride, just as it was gearing up to celebrate its 30th anniversary, was a poignant example. “If you have these rights, don’t take them for granted. Cherish them, talk about them and protest for them, because there are always new people who have to hear your message.”

When the Guardian visited Budapest last month, sitting down with people in offices, coffee shops, and dining rooms, a note of hope threaded through many interviews.

With elections slated for spring 2026, Orbán is facing an unprecedented challenge from a former member of the Fidesz party’s elite, Péter Magyar. Several recent polls suggest that, if the trend continues, Orbán could lose his grip on power.

“For the first time in 15 years, there is a serious contender,” said Péter Erdélyi, the founder of the Budapest-based Center for Sustainable Media. With hope, however, comes risk: now was, he said, a dangerous moment for anyone perceived to be standing in Orbán’s way.

This year the prime minister said he would “eliminate the entire shadow army” of foreign-funded “politicians, judges, journalists, pseudo-NGOs and political activists”, suggesting he could go further than previously used tactics such as smear campaigns, relentless audits and physical intimidation by Fidesz supporters.

Orbán’s party seemingly made good on the threat when it put forward legislation that would give authorities broad powers to, in the words of one rights organisation, “strangle and starve” NGOs and independent media it sees as a threat to national sovereignty.

The draft law, said Transparency International, marked a “dark turning point” for Hungary. “It is designed to crush dissent, silence civil society, and dismantle the pillars of democracy,” the organisation said.

The Hungarian Helsinki Committee issued a similar warning. “If this bill passes, it will not simply marginalise Hungary’s independent voices – it will extinguish them,” said thhe co-chair Márta Pardavi.

The situation in Hungary had been made more complicated by Trump’s ascension to the White House, said Erdélyi.

“The US government, almost regardless of who occupied the White House, was a moderating force on authoritarians pretty much everywhere but certainly in central Europe,” he said. “And the new White House, of course, is not only not interested in being that, but it is also turning away from the transatlantic relationship or multilateralism in general.”

Magyar’s swift rise has shaken Hungarian politics, according to Miklós Ligeti of Transparency International Hungary, who credited the politician and his movement, Tisza, for catapulting corruption to the top of Hungarians’ concerns.

Through his savvy use of social media and rallies that have drawn thousands, Magyar has repeatedly linked underperforming public services such as healthcare and schools to the country’s soaring levels of corruption.

“Now people start to understand that the serious underfunding of these two services is somehow linked to the fact that the government is spending taxpayers’ money on the enrichment of certain business entrepreneurs who have good ties with the government,” said Ligeti.

While Orbán and his party had long been able to deflect criticism by pointing to the country’s strong economy, this was no longer the case, sparking questions as to how they keep their grasp on power, said Márton Gulyás, a left-leaning political commentator who helms Partizán, the country’s most-watched political YouTube channel.

“I think right now they are in a very dangerous phase, mostly because of the tremendous problems in the economy,” he said. “They’re losing money heavily on debt, inflation is still high, food prices are still high and wages have stagnated.”

He said the unprecedented political challenge has been heightened by new models of journalism that had learned to evade Orbán’s heavy hand, from Gulyás’s YouTube channel, which employs 70 people, and independent outlets such as 444, Telex, and 24.hu.

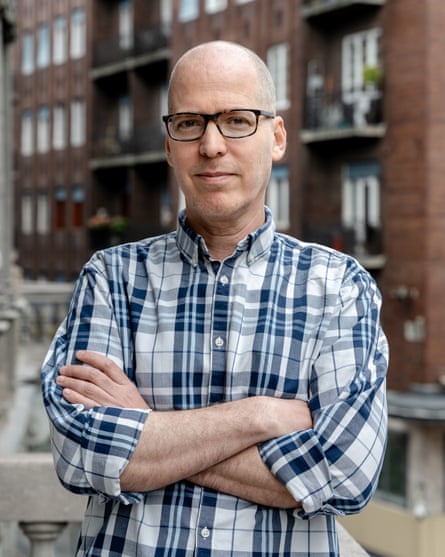

Among them was András Pethő, who left his newsroom a decade ago after it became evident the publisher was under growing pressure to toe the government line. When he cofounded the investigative media outlet Direkt36, he knew the model had to be different.

“We set up this organisation in a way that would be more resilient against these kinds of pressures,” said Pethő as he drove to Szombathely, a small city in the west of Hungary where Direkt36 was screening a documentary on the lavish business dealings linked to Orbán’s family since he took power.

The event was an example of how journalists are forging direct, grassroots connections with audiences across Hungary. “We don’t have investors, we don’t have a corporate owner, because we saw that that’s how pressure is exerted,” Pethő said.

In recent years there have been many warnings about the Hungarian government’s erosion of democracy. In 2018, it was accused of trying to “stop democracy” after it passed a law criminalising lawyers and activists who help asylum seekers.

Four years later, members of the European parliament backed a report outlining why Hungary could no longer be considered a full democracy. Most recently, a delegation of EU lawmakers called on Hungary to return to “real democracy” after a visit to the country.

Although Hungary may serve as a model of sorts for the US, many in Budapest questioned whether the same impact was possible across the Atlantic.

“I think the intention is similar,” said Erdélyi of the Center for Sustainable Media. But Hungary’s economy relies heavily on outside forces; it is not a global superpower. “It’s easy to centralise here because there’s not that much stuff to centralise.”

The sentiment was echoed by Zoltán Ádám, a senior research fellow at the Centre for Social Sciences. “Once you build a two-thirds majority in parliament, you are basically ruling the world in this country,” he said. “So you can introduce a monarchy or make Viktor Orbán’s uncle the champion of whatever sports competition – I’m joking, but it’s just half a joke.”

This majority allows Orbán and his backers to rewrite the country’s laws at will to serve their own political purposes. “This is a fully controlled country to a large extent,” said Ádám. “This is not totalitarian in the 20th-century sense, this is not a Bolshevik or a fascist system, but all the major institutional actors in the country are actually controlled by the government.”

In the US, in contrast, the federal nature provided a built-in system of checks and balances that should protect the country against this sort of threat, said Ádám. “Trump doesn’t control the governor of Massachusetts or the state house of California.”

Others questioned how Hungary had come to be seen as a model for the US. “It’s funny because this is a narrative that was built up by Viktor Orbán’s circles,” said a former Fidesz politician who left the party decades ago after becoming disillusioned with Orbán’s leadership.

“It’s a story that was sold to the Americans,” said the former politician, who asked not to be named, referring to reports that have alleged that the Hungarian government spent millions of euros on intermediaries tasked with selling the US a specific image of Orbán and Hungary.

“They sold it in a very smart way because they used American terms that don’t have much sense in Hungary,” she said. “So like ‘gender war’, ‘woke’ – there’s no ‘woke’ issue in Hungary. Hungary is much more behind in terms of progressivism than the United States … Hungary’s not even a multicultural country; it’s very homogenous in every sense.”

For 15 years she has watched Orbán tighten his grip on power. The longer it went on, the greater Orbán’s motivation would be to cling to power at any cost, she warned. “The system only works for them if they are in power, because they create their own rules. They know that all the rules will change if they lose power.”

Her comments came days before it emerged that Hungarian officials had asked the European parliament, for the third time, to lift Magyar’s immunity as an MEP. Magyar described it as an attempt by Orbán and his party to levy false charges against him and block him from running in next year’s elections.

The Hungarian government was approached for comment for this article, but a representative cited time constraints and declined to meet. The possibility of speaking with someone from a government-linked institute was then floated, before the Guardian was told that they would have no time to speak either in person or over the phone.

Just how much Orbán and his party’s views line up with those of his counterparts in the US remains a matter of debate. Orbán had long cultivated an image of himself as a stalwart of conservative values, using it as a cover to ease his access to the US administration, said the investigative journalist Szabolcs Panyi.

“Orbán just uses this as a smokescreen,” he said. “I think he just invented these pro-family, anti-migration policies; it’s something that he can advertise as a common denominator among all of the conservative groups in the world.”

“But in reality, what makes Orbán really powerful and interesting … is everything that is going against the US Republican values and policies,” he added, pointing to Hungary’s full state control of certain industries and Orbán’s heavy reliance on Chinese industry and technology and Russian fossil fuels.

In recent weeks, analysts have warned that Orbán’s ties to Trump could begin to work against him if the US president’s tariffs hurt the country’s economy.

If Orbán’s hold on power were to be weakened by Trump, it would be a tremendous irony, said Panyi.

“It could be Orbán’s tragedy. That by the time that all the stars align when it comes to foreign policy, by the time he reaches that level where he can legitimately claim that his comrades are on the rise and there’s a far-right wave and he’s been spearheading it, at least ideologically, that by that time his domestic support is crumbling.”